CWD is Moving

Chronic wasting disease (CWD) is a big deal for deer populations, deer management, and deer hunting — and for many reasons. First, it’s a threat to white-tailed populations throughout the deer’s range. Secondly, it is a huge point of contention between hunters and deer breeding operations as well as hunters and state natural resource agencies. The fact is that nobody really knows how CWD will impact free-ranging deer herds over the long term.

It’s a little disturbing for those of us that enjoying hunting white-tailed deer in the fall and consuming venison throughout the year with our families. At a time when the importance of recruiting new hunters is much of what we hear and read about, CWD itself, or the resulting management of the disease, may potentially push current and additional, potential hunters away. Who knows?

Fast-Tracking CWD Transmission

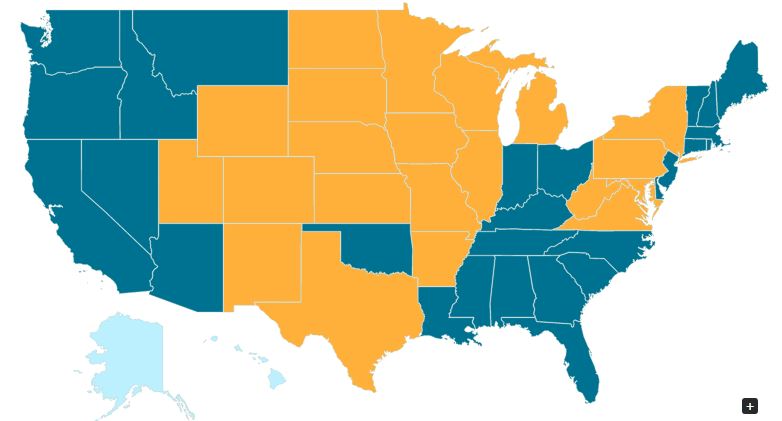

What is known: CWD is fatal to any deer that gets it. It’s a naturally occurring disease. Infected animals can infect other animals. Healthy animals can become infected while living in an infected environment. The rate of spread from one area to another can be increased by people moving deer infected with CWD. CWD has been found in 23 states, to date.

It’s generally thought that older bucks are the CWD-prone animals, but new research suggests that does are more likely than bucks to spread CWD within their range. According to reports of the study:

Fewer female white-tailed deer disperse than males, but when they do, they typically travel more than twice as far, taking much more convoluted paths and covering larger areas, according to researchers in Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences.

These findings, from a study in which 277 juvenile female deer were fitted with radio collars, has important deer-management implications in states where chronic wasting disease is known to be infecting wild, free-ranging deer, noted researcher Duane Diefenbach, adjunct professor of wildlife ecology.

“Dispersal of female deer is density dependent, meaning that higher deer densities lead to greater dispersal rates.” He explained. “Therefore, reducing deer density will reduce female dispersal rates—and likely will reduce disease spread.

CWD More Likely in Bucks

Past studies have shown that older bucks are more likely to have CWD, to test positive for it. This makes sense to me because even though the new research out of Pennsylvania suggest that does are more likely to spread the disease through dispersal, bucks likely encounter more does during the breeding season, which increases their chances of contracting the fatal disease.

It’s been suggested that bucks be targeted by hunters to slow the spread, but no one can say for sure whether or not this strategy has worked or will work for sure. In Wisconsin, yearling bucks and does were found to have CWD at a similar rate, about 3.5 percent, in areas where the CWD disease was “most prevalent.” Those are only year-and-a-half old deer, which means both sexes are going to test out at significantly higher rates as they age.

The Penn State research gives some merit to herd reduction plans commonly implemented by state natural resource departments throughout the US; a decrease in deer density and shorter dispersal distances will reduce the rate of spread of CWD within deer populations. It’s paramount that it be pointed out that the end result is still fewer deer. CWD itself, or the control strategies implemented to reduce the spread of the disease, both lead us to the same end-point, reduced deer numbers, reduced hunter opportunity and a continued decline in hunter recruitment.

Scientists believe that the prions that cause CWD in white-tailed deer can persists for years, maybe even decades, in the soils in areas that have become infected — even after all of the deer are gone. If we remove all of the deer to prevent the spread of the disease, then what will we be left with?

Fortunately, CWD kills deer slowly. In fact, it’s been reported that a deer must have CWD for almost a year before it will even test positive for the disease. CWD is always fatal to a deer, but since it works slowly the biggest initial threat to most management programs will be reduced age structure in bucks. Even fewer bucks will reach old age as the disease becomes more prevalent, assuming hunting pressure remains constant. That’s a big assumption. Only time will tell.