Screwworms in Deer: A Parasite of Whitetail

Screwworms in deer are a big deal. In fact, screwworms nearly wiped out southern deer herds in the mid-20th century due to a devastating infestation of the New World screwworm (Cochliomyia hominivorax). The screwworm is a parasitic fly that infects deer and other mammals. Fortunately, the parasite was eradicated from the U.S. in 1966. However, it came with costly efforts by state and federal animal health officials, livestock producers, and veterinary practitioners.

Officials are now concerned that screwworms may return in earnest to the U.S. in the near future. Eradication efforts have continued in Central America, but the pest is considered widespread in Cuba, Haiti, Dominican Republic and South American countries. A return to the U.S. would not bode well for white-tailed deer and other mammals, including humans.

History of Screwworms in Deer & Other Animals

The New World screwworm nearly eliminated white-tailed deer in the southern U.S. However, a concerted effort by officials flipped the script about 75 years ago. Research was put into action to eradicate screwworms, saving deer and livestock. Unfortunately, screwworms returned to the U.S. more recently.

In 2016, the screwworm again reared its ugly head in Florida in the fall of 2016. Fortunately, The USDA and Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services used a biological control technique to eradicate the screwworms by March 2017. This was a short-live episode, but almost 150 endangered Key Deer fell to screwworms before the parasite was once again knocked out.

Will screwworms return again? Maybe. Here is the history of screwworms in deer in the U.S. and how white-tailed deer populations at lower latitudes were saved, twice.

New World Screwworm Lifecycle

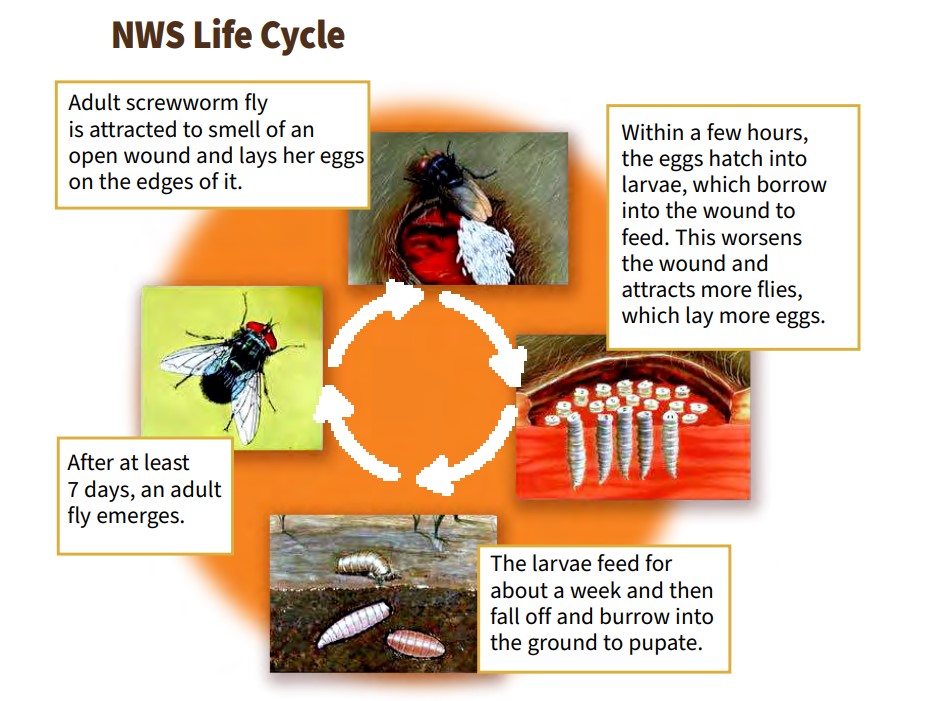

The screwworm fly lays its eggs in open wounds of warm-blooded animals, including deer. The larvae that hatch from these eggs burrow into the flesh, feeding on the tissue. This causes severe, often fatal infections, as the larvae can continue to feed and grow, eventually killing the host animal if not treated.

Spread of the Screwworm Infestation

In the 1950s and 1960s, the screwworm problem spread rapidly in the southern United States. Deer populations, which were already recovering from earlier hunting pressures, became highly vulnerable to these parasitic infestations. Since deer often wander in environments where they might get small injuries—such as from thorns or other natural causes—the flies found abundant opportunities to infest them.

Massive Mortality by Screwworms in Deer

The infestation led to a high mortality rate among deer. Female screwworms could lay hundreds of eggs in a single wound, and because of the flies’ ability to quickly multiply, entire herds of deer could be devastated in a short amount of time. In some areas, screwworm infestations were so widespread that local deer populations faced significant declines.

Efforts to Control Screwworms

The response to the screwworm crisis involved several methods, but the most notable was the sterile insect technique (SIT). This approach involved mass-producing male screwworms, sterilizing them through radiation, and releasing them into the wild. These sterile males would mate with females, but no larvae would be produced, thereby reducing the screwworm population over time.

Success of Eradication

By the early 1970s, the combination of SIT and other control measures led to the eradication of screwworms from the southern United States. The deer population began to recover. In fact, herds were able to rebuild even although the threat of screwworms remained a concern for some time.

In short, screwworms nearly wiped out southern deer herds in Texas and beyond due to their parasitic nature, which led to high mortality rates in vulnerable deer populations. The situation was eventually controlled through a coordinated effort, including the use of sterilized flies to break the breeding cycle. Now, they may return to the U.S. and we may find screwworms in deer yet again.

Screwworms Return to the U.S.

Wildlife officials in Texas are asking hunters and other outdoor enthusiasts in South Texas to monitor for animals affected by New World Screwworm after a recent detection in Mexico. This detection, found in a cow at an inspection checkpoint in the southern Mexico State of Chiapas, close to the border with Guatemala, follows the progressively northward movement of NWS through both South and Central Americas.

As a protective measure, animal health officials ask those along the southern Texas border to monitor wildlife, livestock and pets for clinical signs of screwworms and immediately report potential cases.

What is New World Screwworm?

New World screwworms (NWS) are larvae or maggots of the NWS fly that cause a painful condition known as NWS myiasis. NWS flies lay eggs in open wounds or orifices of live tissue such as nostrils, eyes or mouth. These eggs hatch into dangerous parasitic larvae, and the maggots burrow or screw into flesh with sharp mouth hooks. Wounds can become larger, and an infestation can often cause serious, deadly damage or death to the infected animal.

Screwworms primarily infests livestock but can also affect humans and wildlife including deer and birds. Clinical signs of NWS myiasis may include:

- Irritated or depressed behavior

- Loss of appetite

- Head shaking

- Smell of decaying flesh

- Presence of fly larvae (maggots) in wounds

- Isolation from other animals or people

- Transmission

Screwworms infestations in deer and other mammals begin when a female screwworm fly is drawn to the odor of a wound or natural opening on a live, warm-blooded animal, where she lays her eggs. These openings can include wounds as small as a tick bite, nasal or eye openings, navel of a newborn or genitalia.

One screwworm female fly can lay up to 300 eggs at a time and may lay up to 3,000 eggs during her lifespan. Eggs hatch into larvae (maggots) that burrow into an opening to feed. After feeding, larvae drop to the ground, burrow into the soil and emerge as adult screwworm flies. Adult flies can fly long distances and the movement of infested livestock or wildlife can increase the rate of spread. So, if officials find screwworms in deer populations, the spread and impact can be severe.

How to Help: Monitoring Screwworms

While in the field enjoying activities such as deer hunting, hiking or bird watching, hunters and outdoor enthusiasts are asked to report suspected signs of NWS. Any wildlife with suspicious clinical signs consistent with screwworms should be immediately reported to a local Texas Parks & Wildlife Department biologist. Livestock reports should be made to the Texas Animal Health Commission or U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Obviously, the potential return of screwworms in deer and livestock is of great concern to hunters, agricultural producers, and the general public. While there is not much that can be done currently, the first step is detecting the presence of the parasite in the U.S, should it arrive. Even though we’ve beat screwworms twice in the U.S., let’s hope it does not have to be done again.