CWD from Venison

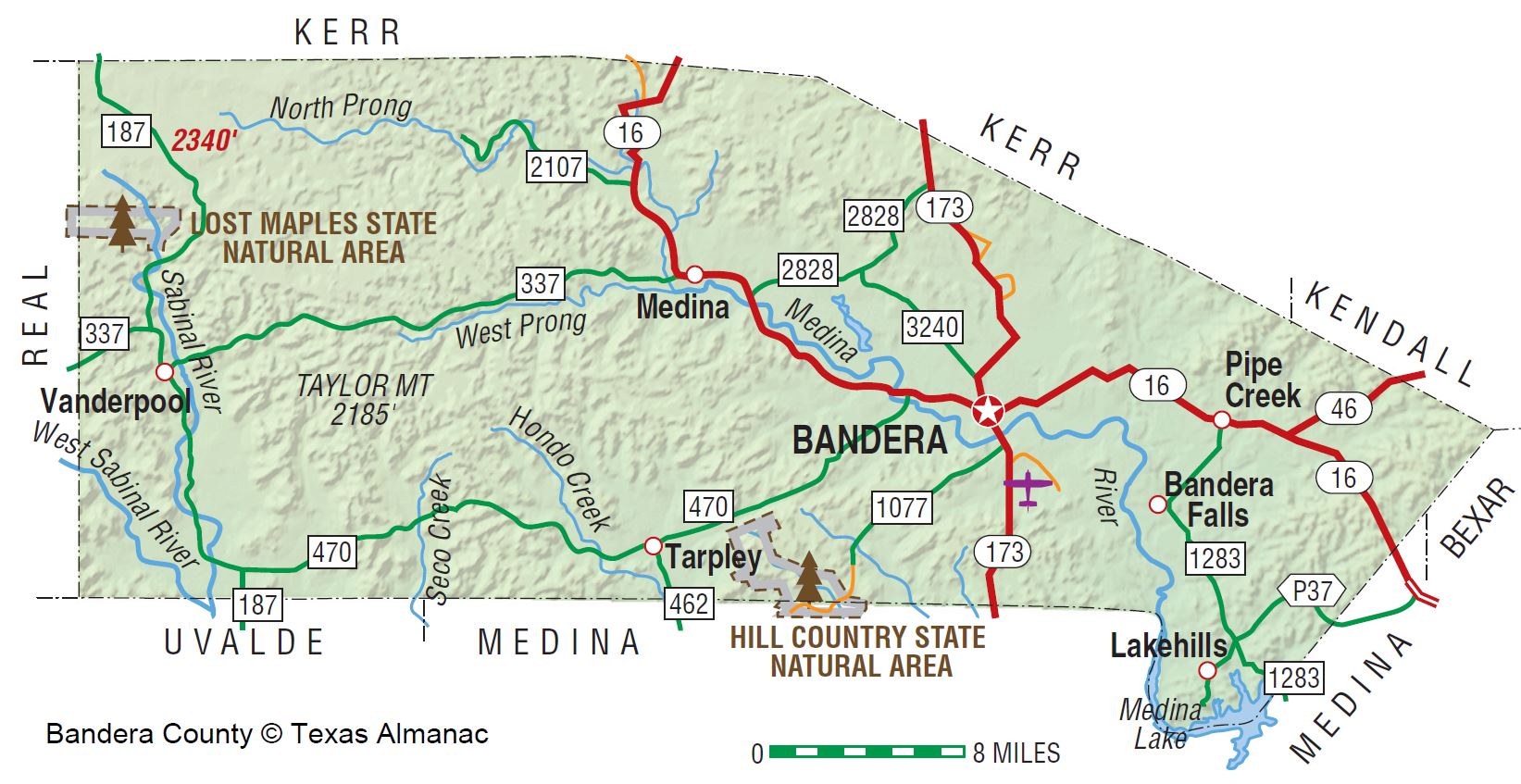

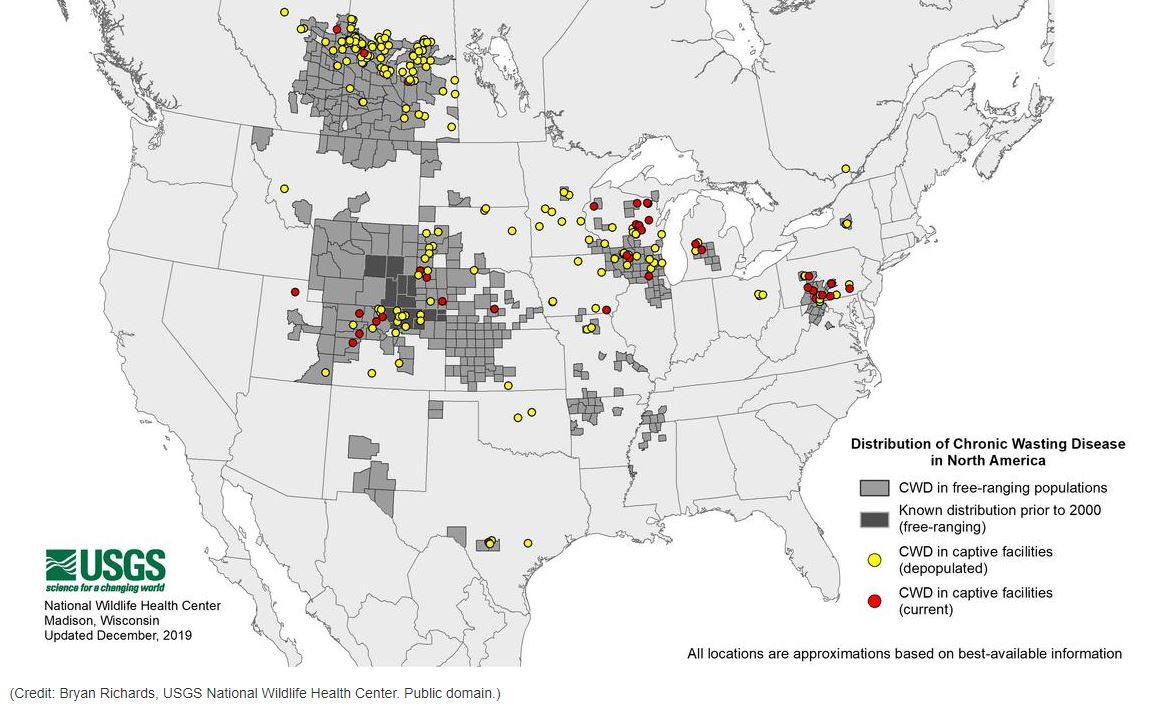

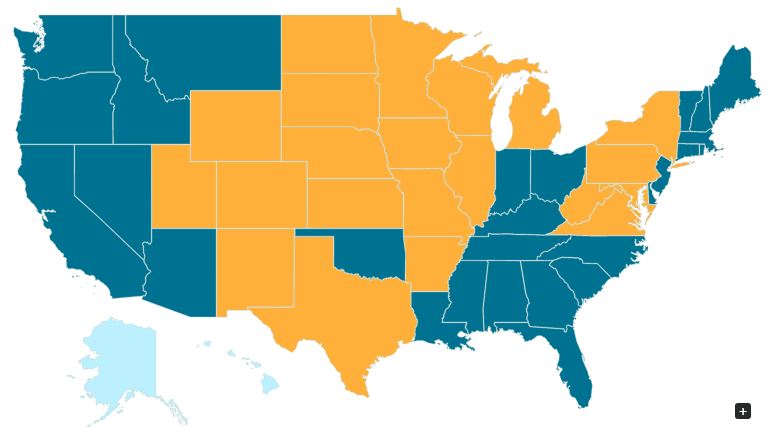

The biggest thing to hit the deer hunting world in recent years has been the increasing prevalence of Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) in white-tailed deer herds across the US. Unfortunately, the disease not only threatens our great natural resources, but also poses a threat to hunters.

Although there is no evidence that directly links CWD to specific illnesses in humans, there are also no long-term studies that examine those relationships either. Anyone been tested for CWD lately?

Make no mistake, CWD is a huge issue that impacts cervids, natural resource agencies, hunters and the our hunting heritage. The long-term impacts of the disease on deer hunting and hunter recruitment are completely unknown. Will CWD extirpate the deer or those that choose to hunt them first?

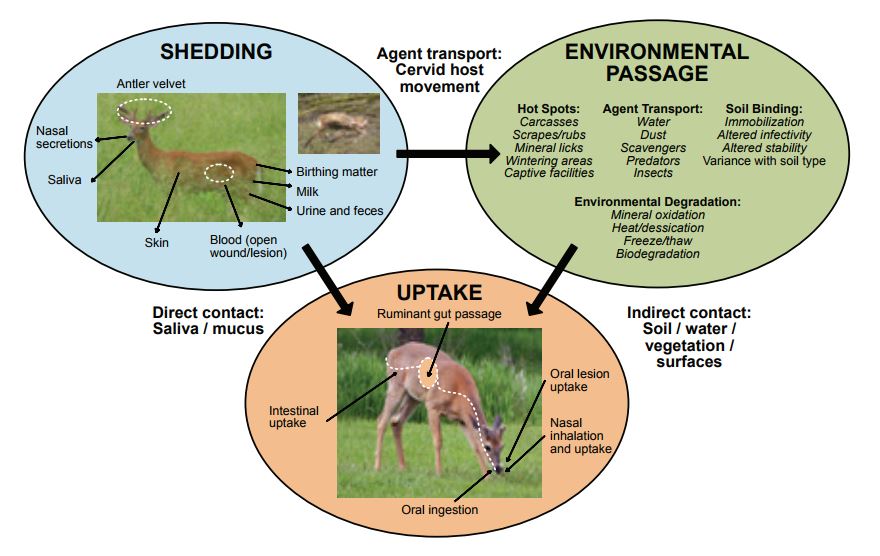

Ingesting CWD

Having to consider whether or not to eat CWD-infected venison is not something that most hunters have to deal with, yet. But in a number of states, the chances of harvesting a deer infected with CWD are rising. In parts of Wisconsin, for example, infection rates on tested deer are coming in at 30 percent.

Though some experts believe there is a “species barrier” that may prevent humans from getting CWD, other experts suggest that any perceived barrier is not absolute. And after exposed to the prion, the incubation period (the time it takes to see impacts from the disease) is anyone’s guess.

A past study found that monkeys remained free of CWD 6 years after being “exposed orally and intracerebrally,” but researchers have just reported that primates, a classification (order) that includes monkeys, apes and humans, did contract the disease after eating venison that contained CWD prions.

Can Humans Get CWD?

Source: Macaque monkeys contracted chronic wasting disease after eating meat from CWD-positive deer, according to Canadian researchers.

The findings are the first known oral transmissions of the prion disease to a primate and have heightened concerns of human susceptibility to CWD.

“The assumption was for the longest time that chronic wasting disease was not a threat to human health,” said Stefanie Czub, prion researcher with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, in remarks published June 24 in The Tyee, a Vancouver, B.C. magazine. “But with the new data it seems we need to revisit this view to some degree.”

Czub is leading the project, which began in 2009 and is funded by Alberta Prion Research Institute at the University of Calgary.

Eighteen macaques, a type of monkey, have been exposed to CWD in various ways to study the zoonotic potential of the disease.

Three of five macaques that were fed infected white-tailed deer meat over a three-year period tested positive for CWD.

The meat fed to the macaques represented the human equivalent of eating a seven-ounce steak per month.

Macaques that had the CWD prion injected into their brains also contracted the disease.

Those that had infected material rubbed on their skin – designed to simulate contact a hunter might have while field dressing a deer – have not contracted the disease.