White-tailed deer diseases are common. Although most only result in minimal impacts on a local deer population, some deer diseases can can have a severe impact on deer hunting and management activities. Anthrax is one of the diseases that is really good at making deer dead. This bacterial disease not only kills deer, but all other mammals as well. The Texas Animal Health Commission (TAHC) announced in a news release last week that the first confirmed case of anthrax in a Texas animal for 2012 has been detected in a whitetail buck in Uvalde County.

An anthrax outbreak occurred on June 6, 2012, and involved 10 dead white-tailed deer on a newly purchased ranch approximately 20-25 miles north of Uvalde, Texas, on Highway 55 (to Rocksprings). There was one freshly dead deer when the veterinarian visited the ranch, and this was the one he sampled and sent to the Texas Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory in College Station for confirmation. Information from that sample spurred TAHC’s anthrax news release. The high fenced ranch where the anthrax outbreak occurred has both whitetail and exotics deer species. There are no livestock grazing on the property and the size of the ranch is not available at this time.

The 10 deer are said to have died over a two day interval. This tells me that there are already other prior cases in that general area that either no one is talking about (not unusual), or they have yet to get out and check their stock and watch the vultures. The fact that “ten” deer were affected essentially at once would confirm fly activity, because in dry years, it is usually just single or double deaths and no follow through. The flies feed on an index case, and then with contaminated mouthparts feed on other deer, mammals nearby. From the nature of commercial deer breeding in Texas, the deer density is high, as they are frequently fed with protein pellets or cracked corn at multiple feeding stations, so the female flies do not have trouble finding another deer to feed upon, infect and kill.

The new ranch owner had been moving dirt, as new owners often do, and it is theoretically possible he had disturbed an old anthrax grave site, which, with the recent four to six inches of rain, the turned soil could have sprouted some tasty deer foods. Though normally browsers, whitetail deer will graze on fresh, succulent grasses. Anthrax outbreaks based on grazing usually start with a single affected animal from which the infection spreads. Ten “at once” is not likely to be from grazing, but the full story has yet to unfold.

Because of the increase in rainfall in early May 2012 in the area bounded by Interstate 10 and Interstate 90, essentially between Uvalde and Sonora, Texas state veterinarians had been warning the local deer ranchers of the risk from a sudden tabanid hatch and resulting anthrax outbreaks involving numbers of animals. Additionally, they have been reporting a lot of flies in the area. Unfortunately, it looks like they have been correct their prediction about this deadly deer disease. Expect an active summer in this part of Texas, where wildlife anthrax is endemic.

TAHC News Release:

“Anthrax Case Confirmed in White-tailed Deer near Uvalde

The first confirmed case of anthrax in a Texas animal for 2012 has been detected in an adult white-tailed male deer near Uvalde (Uvalde County). At this time no domestic livestock are involved.

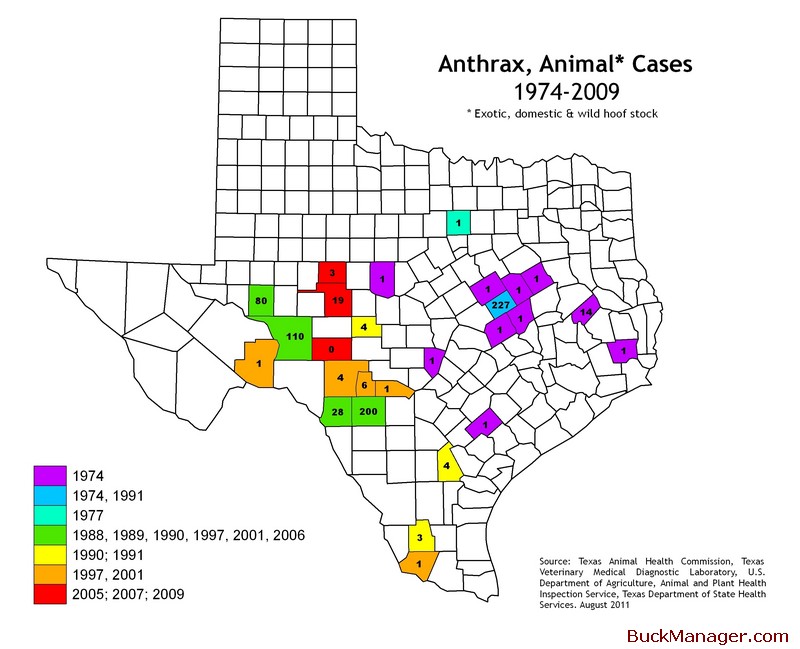

Anthrax is a bacterial disease caused by Bacillus anthracis, which is a naturally occurring organism with worldwide distribution, including Texas. It is not uncommon for anthrax to be diagnosed in livestock, whitetail deer or other wildlife in the Southwest part of the state. In recent years, cases have been primarily confined to a triangular area bounded by the towns of Uvalde, Ozona and Eagle Pass.

“The TAHC will continue to closely monitor the situation for possible new cases across the state. Producers are encouraged to consult with their veterinary practitioner or local TAHC office about the disease,” Dr. Dee Ellis, State Veterinarian, said. For more information regarding anthrax, visit the Texas Animal Health Commission website or call 1-800-550-8242.”